Jeremy Deller

Iggy Pop Life Class

Brooklyn, USA: Brooklyn Museum, 2016

144 pp., 8.5 x 11.5", softcover

Edition size unknown

“The life class is a special place in which to scrutinize the human form. As the bedrock of art education and art history, it is still the best way to understand the body,” says Jeremy Deller. “For me it makes perfect sense for Iggy Pop to be the subject of a life class; his body is central to an understanding of rock music and its place within American culture. His body has witnessed much and should be documented.”

In February of 2016, Deller hosted a life drawing class at the New York Academy of Art. The class was led by drawing professor and visual artist Michael Grimaldi and the nude artist model was 69 year old Iggy Pop.

Twenty-one artists, from all walks of life and educational backgrounds, participated in the project. They ranged in age from 19 to 80. Some were current undergraduate and graduate students, others were practicing artists, some had retired.

In total, 107 drawings of Iggy Pop were produced, ranging from five-minute sketches to studies to presentation drawings. All are included in Iggy Pop Life Class, which was published on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name at Brooklyn Museum. The book also features an introduction by Deller, an interview with Pop, and an essay on the practice of life drawing in art history, documentation of the process, and works from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

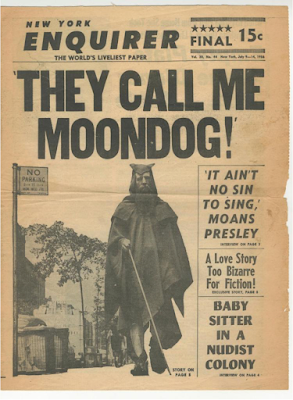

The promotional poster for the project (below) inverts the structure of a life drawing class by having the model clothed and those sketching naked.

Iggy Pop Life Class us available here, for £19.99.