Joseph Kosuth celebrates his 79th birthday today.

Tuesday, January 30, 2024

Jan Steele / John Cage | Voices And Instruments

Jan Steele / John Cage

Voices And Instruments

London, UK: Obscure Records, 1976

12” vinyl record

Edition size unknown

John Cage notoriously avoided recorded music (he didn’t own a record player, preferring the sounds of the open window) and there’s no indication that he had any part in this disk. More likely is that Brian Eno felt a series of “contemporary classical" records with a conceptual bent should probably include him in some way.

Cage’s 1942 work, The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs (a song for voice and closed piano) was initially commissioned by soprano and socialite Janet Fairbank. Cage appropriated a text from page 556 of James Joyce's 1939 book Finnegans Wake, condensing and rearranging it. It marks the first instance of Cage working with Joyce’s writings, something that would continue for another forty-five years.

“Even though I owned a copy, no matter where I lived, the Wake simply sat on a table or shelf unread. I was ‘too busy’ writing music to read it,” Cage said, "I loved it without reading it for 37 yrs!”

The vocal line only uses three pitches, and the piano remains closed. The pianist produces sounds by hitting the lid or other areas of the instrument with their fingers or knuckles. This calls back to the Prepared Piano works of the previous decade, and forward to his masterpiece, 4’33”, still a decade away.

For this recording the song is sang by Robert Wyatt, the former Soft Machine and Matching Mole vocalist. Wyatt and Eno would continue to until the former’s retirement in 2014.

Joey Ramone performed The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs for Cage Uncaged, a 1993 tribute, which also included contributions by David Byrne, John Cale, Fred Frith, Debbie Harry, Lee Ranaldo, Lou Reed, John Zorn, and others. His version can be heard here.

Cage wrote Forever and Sunsmell for dancer Jean Erdman. The work is for a singer and two percussionists. The singer is instructed to sing in a non-operatic manner, to avoid using vibrato, and is given wide latitude regarding the pitch of the melody. The percussionists play two Chinese tom-toms and one large suspended Chinese cymbal.

The text is from e.e. cummings' 1940 collection 50 Poems, using lines from the poem designated as “twenty-six". The borrowed lines of poetry are supplemented by an interlude of humming.

On Voices And Instruments the work is sang by Jazz legend Carla Bley.

That’s the first half of the Obscure Records (and Obscure Records box set). The second will resume shortly.

David Toop / Max Eastley | New And Rediscovered Musical Instruments

David Toop / Max Eastley

New And Rediscovered Musical Instruments

London, UK: Obscure Records, 1975

12” vinyl LP

Edition size unknown

Released on December 5th, 1975 (alongside Obscure Records #1, 2 and 3), New And Rediscovered Musical Instruments features four tracks from Max Eastley on side A and three from David Toop on side B.

“Brian suggested an array of five stereo microphones on stands to record the sound of the [kinetic sculpture] Metallophone, producing multi-channels on the studio mixer. I realized that the instrument had been transformed into another medium where choices could be made regarding dynamics and equalization. We made two recordings: one by Brian and one by me. Brian said he liked the first part of my recording and the second part of his and so this is what finally appeared on the record.”

- Max Eastley, 2023

"At that time, '73 and' 74, I became aware that there were a number of us making instruments. Max Eastley was a good friend and he was making instruments, Paul Burwell and I were making instruments, Evan Parker was making instruments, and we knew Hugh Davies, who was a real pioneer of these amplified instruments. Paul and I had also got interested in making books. We’d been working with Bob Cobbing, the sound poet, since the beginning of the 70s, and Bob had this press called Writers Forum. And Bob would do a book in an evening: Christmas Day, he’d do a book. He was just like, “Do you want to do a book?” “Yeah, OK,” “Let’s get going” – he was that kind of character. It was very inspiring to us – we were much younger, of course. But it made us realise you can do this. Never mind that nobody’s interested in it in the mainstream media.

I had the idea to do an anthology about instrument-making. At that time, Paul was at Ealing College of Art, studying art: basically, he was doing that to use the facilities. In other words, if we wanted to do a book, then we could do it there.

What happened after that? I think I sent one to Brian Eno. I don’t know how I got to know his address, but I sent one to him. He called me up and he said, “I really like the book, and I’m starting a new label, would you liked to do something?” It was a tricky situation for me, because I’ve always had this thing in my life of a tension between collaboration, which was extremely important to me, and then being alone. Make of that what you will! I think Paul and I had come to the end of a phase of working together. We were very close, we were sort of like brothers in a way, but I was beginning to feel I wanted to do something beyond that. So, I think what I did really was quite dishonourable, in the sense that I said to Brian, “Well, I want to do it solo.” It’s one of those things in my life I’m not particularly proud of. But I had ideas about music and sound and listening and time and so on that I wanted to pursue as an individual, and by doing that book, Brian opened the door, and he decided to do a record based loosely on the book, and Max was the obvious candidate. In fact, I asked Paul, and Hugh Davies, who was also in the book, to play, and Paul graciously agreed to that. It makes me feel even guiltier.

I was at a time of my life of making choices, I suppose: am I a writer, am I a visual artist? And when I was a teenager. I thought I would be a film-maker. Am I a musician? If so, what kind of musician am I?”

- David Toop, 2016

Monday, January 29, 2024

Brian Eno | Discreet Music

Brian Eno

Discreet Music

London, UK: Obscure Records, 1975

12” vinyl LP, 54:07

Edition size unknown

On January 18th, 1975, Brian Eno was walking in the rain as it turned to sleet, and slipped and fell into the road. He was hit by a taxi cab, knocking him backwards to hit his head on the bumper of a parked car. He was hospitalized, but discharged himself after a week to convalesce at home.

"I was not seriously hurt,” he writes in the liner notes to Discreet Music, "but I was confined to bed in a stiff and static position. My friend Judy Nylon1 visited me and brought me a record of 18th century harp music. After she had gone, and with some considerable difficulty, I put on the record. Having laid down, I realized that the amplifier was set at an extremely low level, and that one channel of the stereo had failed completely. Since I hadn't the energy to get up and improve matters, the record played on almost inaudibly. This presented what was for me a new way of hearing music - as part of the ambience of the environment just as the colour of the light and the sound of the rain were parts of that ambience. It is for this reason that I suggest listening to the piece at comparatively low levels, even to the extent that it frequently falls below the threshold of audibility."

The tale has taken on legendary status as the origin story of ambient music, but Nylon disputes the account (see below) and Eno’s retellings are inconsistent. In an 2011 interview he states "Judy put a record on and then left. The record was much too quiet but I couldn't reach to turn it up and it was raining outside ... I suddenly thought of this idea of making music that didn't impose itself on your space ... but created a sort of landscape you could belong to".

Music For Airports, released three years later and subtitled Ambient #1, is typically credited as the first and best ambient album (Pitchfork ran a ten-star review only a couple of weeks ago). It’s indeed excellent, but Discreet Music came first and is ultimately the more satisfying album.

I first bought the record when I was in high school, a vinyl copy from a used record store, and played it nightly as I fell asleep, for weeks.

This was around the time that the Grammys introduced a new award for Best New Age Music. Eno certainly shoulders some of the blame for the popularity of that genre, but 99% of it struck me then (and now) as vacuous and insipid.

Discreet Music, on the other hand is rich, beautiful and placid. The melody line is infectious and slippery, like the best pop music hooks. And conceptually solid.

The first sentence in the liner notes might as well be a conceptual art manifesto, akin to Lawrence Weiner’s In Relation To Probable Use (below)2 :

"Since I have always preferred making plans to executing them, I have gravitated towards situations and systems that, once set into operation, could create music with little or no intervention on my part. That is to say, I tend towards the roles of the planner and programmer, and then become an audience to the results.”

The liner notes (reprinted, twice, in the new box set reissue) continue:

"Two ways of satisfying this interest are exemplified on this album. "Discreet Music" is a technological approach to the problem. If there is any score for the piece, it must be the operational diagram of the particular apparatus I used for its production. The key configuration here is the long delay echo system with which I have experimented since I became aware of the musical possibilities of tape recorders in 1964. Having set up this apparatus, my degree of participation in what it subsequently did was limited to (a) providing an input (in this case, two simple and mutually compatible melodic lines of different duration stored on a digital recall system) and (b) occasionally altering the timbre of the synthesizer's output by means of a graphic equalizer.

It is a point of discipline to accept this passive role, and for once, to ignore the tendency to play the artist by dabbling and interfering. In this case, I was aided by the idea that what I was making was simply a background for my friend Robert Fripp to play over in a series of concerts we had planned. This notion of its future utility, coupled with my own pleasure in "gradual processes" prevented me from attempting to create surprises and less than predictable changes in the piece. I was trying to make a piece that could be listened to and yet could be ignored... perhaps in the spirit of Satie who wanted to make music that could "mingle with the sound of the knives and forks at dinner.”

Along with Satie’s idea of "furniture music”3 and John Cage’s use of chance when composing, Discreet Music borrows from the tape experiments of Steve Reich. Here the left channel sequence is approximately 63.5 seconds, and the right is 68.7 seconds. This difference in length means the loops are asynchronous, taking roughly 15 minutes return to their original alignment.

In a 1979 interview with Lester Bangs, Eno called Obscure #3 the most successful of his recordings, explaining that it "was done very, very easily, very quickly, very cheaply, with no pain or anguish over anything, and I still like it."

"What I liked about it,” he added later, "was the idea that, by fading it in at the start and out at the end, you get the impression that you’ve caught part of an endless process."

It’s unfortunate that the two tracks on Gavin Bryar’s Obscure #1 LP have both been given extended versions that almost triple their original running time, but Discreet Music - which was always advertised as being a selection of a larger work - has never been revisited. It would have made a nice bonus disc for the box set.

1. Judy Nylon is a multidisciplinary American artist who has collaborated with Patti Palladin (as Snatch), Eno, John Cale, Jah Wobble, Adrian Sherwood, Bot'Ox and others. She is the subject of Eno's song "Back in Judy's Jungle” and “Judy Nylon” by Arp.

2. Better still, Robert Filliou’s Principals of Equivalence checklist: Well Made, Badly Made, Not Made.

3. Erik Satie coined the term “Furniture Music” in 1917, to describe music intended to be played in the background. The French term "musique d’ameublement” is sometimes more literally translated as "furnishing music”.

"The anecdote about the inciting incident [the harp record] that started Eno's Discreet Music has been told with several slight variations on the sleeve, in interviews and a number of books over almost 30 years and even translated out of English. According to what I remember, it was inaccurately told, even on the first record sleeve. There were two people in the room, him and me. I could recreate it as if it were written by Robbe-Grillet, but not one interviewer or author has ever asked me my version to this day. It would take a truly modern artist to say, "This is what I remember but you might also ask Judy".

So it was pouring rain in Leicester Square, I bought the harp music from a guy in a booth behind the tube station with my last few quid because we communicated in ideas, not flowers and chocolate, and I didn't want to show up empty-handed. Neither of us was into harp music. But, I grew up in America with ambient music. If I was upset as a kid I was allowed to fall asleep listening to a Martin Denny album…I think it was called "Quiet Village". The jungle sounds, played very softly made the room's darkness caressing instead of empty as a void. Pain was more tolerable. Brian had just come out of hospital, his lung was collapsed and he lay immobile on pillows on the floor with a bank of windows looking out at soft rain in the park on Grantully Road, on his right and his sound system on his left. I put the harp music on and balanced it as best as I could from where I stood; he caught on immediately to what I was doing and helped me balance the softness of the rain patter with the faint string sound for where he lay in the room. There was no "ambience by mistake". Neither of us invented ambient music; that he could convince EG Music to finance his putting out a line of very soft sound recordings is something quite different. We both listened to the early seventies German wave and were influenced by them too.”

- Judy Nylon

Sunday, January 28, 2024

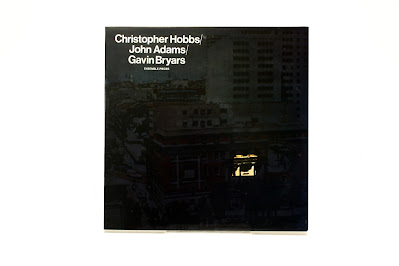

Christopher Hobbs / John Adams / Gavin Bryars | Ensemble Pieces

Christopher Hobbs / John Adams / Gavin Bryars

Ensemble Pieces

London, UK: Obscure Records, 1975

12” vinyl LP, 49:36

Edition size unknown

Ensemble Pieces is the second LP from Brian Eno’s Obscure Records label, issued simultaneously with the first, third and fourth from the series. This release strategy may be responsible for the title getting somewhat overshadowed by the others. It remains one of the least discussed disks in the series, including in the box set’s liner notes.

Like most of the Obscure Records recordings, Ensemble Pieces employs chance compositionally, and involves found sounds.

Gavin Bryars returns (and will again in the third instalment, as the conductor and co-arranger for the b-side of Eno’s Discreet Music) with "1, 2, 1-2-3-4”. The track involves ten performers each wearing headphones which plays only their part. They are instructed to accompany each other, as much as is possible, without hearing them.1 The resulting composition is a kind of dream-like, discombobulated jazz performance.

Christopher Hobbs was a student of Cornelious Cardew, and the youngest member of his infamous Scratch Orchestra. Time Out Magazine (in one of the few contemporaneous reviews of Obscure Records, in 1975) wrote: "Hobbs’ dryly humorous and playful pieces manipulate modest patterns with teasing unpredictability.” Hobbs was twenty-five at the time of the album's release.

John Adams was twenty-eight, and his track American Standard is own of his earliest compositions. He would later go on to success with the release of his first opera, Nixon in China, in 1987.

American Standard consists of three movements of Americana: John Philip Sousa (a march), Christian Zeal and Activity (a hymn) and Sentimentals (a jazz ballad).2

The second is the standout, and apparently the only part of the work performed subsequently, and for which there are published performance materials available. Like both pieces on Obscure #1, it involves a hymn, and - like Jesus’ Blood - a sampled religious voice. The hymn is an arrangement of "Onward, Christian Soldiers”, which I only know from the Flanders’ kids singing it on The Simpsons.

The sample is most notable for me: a "late-night AM radio talk show in which an abusive host argued about God with a patient man who eventually identified himself as a preacher”.

When I think of long form audio works that involve vocal samples, it strikes me that a disproportionate number of them use preachers. This likely began with Steve Reich’s minimalist composition It’s Gonna Rain, from 1965. The sole source material for the now-legendary phased tape piece was a recording Reich made of a young Pentecostal preacher giving a sermon in San Francisco's Union Square, in January of ’65. Brother Walter tells the story of Noah being mocked for the folly of building the ark and seconds into the seventeen minute piece the title phrase is subjected to manual looping and stereo panning experiments.

Brian Eno’s own My Life in Bush of Ghosts, a 1981 collaboration with David Bryne, is often cited as the first use of sampling but was of course predated by early hip-hop, dub reggae producers such as King Tubby and Lee "Scratch” Perry, the Yellow Magic Orchestra, Holger Czukay’s tape-splice recordings and Stevie Wonder's soundtrack to the strange 1979 film The Secret Life of Plants.3

Eno felt the innovation of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, was having the samples samples serve as the "the lead vocal”4. Given the use of a New Orleans broadcast of Reverend Paul Morton (on "Help Me Somebody”) and an unidentified exorcist ("The Jezebel Spirit”), it’s possible the Adams’ piece provided an early germ of the idea.5

Godspeed You Black Emperor’s 1998 song "East Hastings6", also features a passionate preacher preaching. The track begins with the vocal sample: "God love this country, the United States, the world and all the billionaires! If money could buy happiness, my love, then we'll have it. But praise God, it's only salvation, it's only Jesus Christ”, followed by bagpipes, droning and eventually the full band. The voice sets the apocalyptical tone of the eighteen minute epic.7

“Punk Rock”, released a year later by Mogwai, also features distorted found spoken word clip, as the lead in for an album of rock band instrumental crescendos. But instead of a preacher, the vocal sample is of Iggy Pop. The audio comes from an interview in Toronto, with Peter Gzowski at the CBC, broadcast on 11 March 1977. A bewildered Pop was on the show to perform, but at the last minute was prevented from doing so because of union disputes. He does his best to be congenial, but is set off with a question about punk rock, then a brand new musical genre.

He launches into an impassioned tirade:

"I'll tell you about punk rock: 'punk rock' is a word used by dilettantes and heartless manipulators, about music that takes up the energies, and the bodies, and the hearts and the souls and the time and the minds, of young men, who give what they have to it, and give everything they have to it. And it's a it's a term that's based on contempt; it's a term that's based on fashion, style, elitism, satanism, and, everything that's rotten about rock 'n' roll.’ I don't know Johnny Rotten but I'm sure he puts as much blood and sweat into what he does as Sigmund Freud did.”

Re-listening to it now comes the realization that Pop was proselytizing, with all the passion and fervour of a preacher, about his own religion.

1. Glenn Branca, I believe, later employed the headphone technique with choral works, coaxing harmonies from the singers that their ears would naturally force their voices to avoid.

2. "American Standard" was used on the soundtrack of the 2010 Martin Scorsese film Shutter Island.

3. The science behind many of the claims in the film have been debunked, and the title is currently unavailable on disc or streaming services. Without Wonders involvement, it would have likely fallen into complete obscurity. Strangely, it is sometimes held up by conspiracists as evidence that Wonder is not actually blind. I curated a great project by Aislinn Thomas, who screened the film without its image (Louise Lawler style) for an Ontario Culture Days presentation. The soundtrack was then augmented and annotated by Aislinn and her interview subjects.

4. The sample as lead vocal was later popularized by Moby, for better or for worse.

5. During a lecture at the Long Now Foundation, Eno cited Reich’s It's Gonna Rain as his first experience with minimalism and an influence on his later ambient works.

6. The song is named after East Hastings Street in Vancouver's blighted Downtown Eastside. It is often considered the “skid row” of Vancouver.

7. "East Hastings" appeared in Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later and seems to have influenced the rest of the score. For rights reasons, it did not feature on the films soundtrack album.

Gavin Bryars | The Sinking of the Titanic

Gavin Bryars

The Sinking of the Titanic

San Francisco, USA: Superior Viaduct, 2022

Audio CD

Edition size unknown

Once impossible to find, now seemingly everywhere, in a variety of different versions, Bryar’s The Sinking of the Titanic is available on CD from Superior Viaduct.

The label, founded in 2011, has produced a series of reissues of excellent and rare works by Glenn Branca, William Burroughs, Tony Conrad, Jean DeBuffet, David Cunningham, Henry Flynt, Terry Fox, Joe Jones, Takehisa Kosugi, Chris Marker, Phil Niblock, Steve Reich, The Residents, Yoshi Wada, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela and many other artists whose work will have appeared here.

They are also issuing vinyl by musicians, such as Ornette Coleman, Pascal Comelade, The Fall, Brigitte Fontaine, Laraaji, Charles Mingus, Sun Ran, Suicide, Tuxedomoon and the Upsetters.

Visit their site, here.

Saturday, January 27, 2024

Gavin Bryars | Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet [book]

Gavin Bryars

Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet [book]

Rimini, Italy: Luigi Castiglioni Editore, 2021

[80] pp., 50 × 35 cm., slipcase

Edition of 140 signed copies

Renowned bookbinder Luigi Castiglioni began a publishing company a couple of years ago and his first (and thus far only) three projects were with Gavin Bryars. All involve the two tracks on Bryars' Obscure Records disc, The Sinking of the Titanic.

This super-deluxe edition folio features the score letterpress printed on Fabriano Tiepolo 290 gsm, and includes a vinyl record with the song-fragment played as a loop for fifty times, presumably a cappella. It was produced to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the composition.

In a somewhat convoluted structure, some copies also contain a hand drawn artwork and others include a “musical autograph” (?) and one of the letterpress printing plates.

Gavin Bryars | Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet

Gavin Bryars

Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet

Point Music, 1993

Audio CD, 74 minutes

Edition size unknown

A religious hymn that could make an atheist cry (I speak from experience), Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet was originally released as the B-side to The Sinking of the Titanic (Obscure #1), and now rivals it as the work Bryars is best known for.

It’s astonishing that an LP (a debut record, no less) would later have both of its tracks reissued in expanded editions almost twenty years later, each to considerable acclaim. When this CD was released, it topped the Classical charts, selling thousands of copies in the first month of release. According to London’s Daily Star, the HMV megastore on Oxford Street were selling fifty copies a week and rival Tower Records twice that. The disc was subsequently shortlisted for the prestigious Mercury Prize.

It was a time when interest in contemporary ‘classical’ music was high, with recent successes by Henry Gorecki and Avro Part driving interest in the genre.

“I think it all started with opera,” Bryars told the Globe & Mail1 in February of 1994. "Pavarotti recorded Nessun dorma for the World Cup and every time you’d turn on the television you’d hear it. Then Classic FM, a commercial station, took a more populist approach and had a chart show, which had the effect of not only reflecting the way that records were selling, but stimulating it as well”.

The involvement of Tom Waits - arguably at the peak of his popularity, after the Grammy winning Bone Machine2 LP - undoubtedly contributed to this later success, even while it diminished the power of the recording.

Waits had cited the 1975 version as his favourite record of all time, and not just in terms of importance, influence or other academic concerns. He wore out his copy by playing it too often. He contacted Bryars seeking a replacement, and the composer invited him to participate a in a forthcoming re-recording.

Dating back to 1971, the piece was based around a snippet of found sound, a five line hymn, possibly improvised, by a homeless man:

Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet

Never Failed Me Yet

Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet

There’s one thing I know

For He Loved Me So

The singers voice, while weakened by circumstance, is surprisingly solid in terms of pitch (if not tempo, which is irregular in a quite compelling way). His conviction is unshaken and sincere.

“I certainly don’t think of of Jesus’ Blood as a Christian piece,” Bryars told the Toronto Star. “For me, the important thing is the humanity and dignity of the man at the end of his life”.

In this extended version, the voice of Tom Waits takes over, which would be interesting enough in a live setting (triumphant, even, possibly), but as the definitive version of this composition (which this came to be, and the limited edition nature of the box set won’t alter that), it’s an unfortunate addition.

Luckily his voice doesn’t appear until almost the hour mark, after four sections (String Quartet, Low Strings, No Strings and Full Strings). Waits then warbles along for another twenty minutes or so.

The 1993 reissue was initiated by Philip Glass, who started Point Music a year prior, almost certainly influenced by the Obscure Records label. In its ten years of operation it released five recordings by Bryars, along with discs by Jon Gibson, Arthur Russell, Todd Levin, Aphex Twin, Angelo Badalamenti, Bang on a Can (performing Eno’s Music For Airports), the Master Musicians of Jajouka and works by Glass himself.

Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet is still available on CD for $13.29 at Amazon, here.

"In 1971, when I lived in London, I was working with a friend, Alan Power, on a film about people living rough in the area around Elephant and Castle and Waterloo Station. In the course of being filmed, some people broke into drunken song – sometimes bits of opera, sometimes sentimental ballads – and one, who in fact did not drink, sang a religious song "Jesus' Blood Never Failed Me Yet". This was not ultimately used in the film and I was given all the unused sections of tape, including this one.

When I played it at home, I found that his singing was in tune with my piano, and I improvised a simple accompaniment. I noticed, too, that the first section of the song – 13 bars in length – formed an effective loop which repeated in a slightly unpredictable way. I took the tape loop to Leicester, where I was working in the Fine Art Department, and copied the loop onto a continuous reel of tape, thinking about perhaps adding an orchestrated accompaniment to this. The door of the recording room opened on to one of the large painting studios and I left the tape copying, with the door open, while I went to have a cup of coffee. When I came back I found the normally lively room unnaturally subdued. People were moving about much more slowly than usual and a few were sitting alone, quietly weeping.

I was puzzled until I realised that the tape was still playing and that they had been overcome by the old man's singing. This convinced me of the emotional power of the music and of the possibilities offered by adding a simple, though gradually evolving, orchestral accompaniment that respected the homeless man's nobility and simple faith. Although he died before he could hear what I had done with his singing, the piece remains as an eloquent, but understated testimony to his spirit and optimism.”

- Gavin Bryars

1. Bryars was in Winnipeg, presenting the North American premiere of Jesus’ Blood.

2. Tom Waits’ 1992 classic Bone Machine was finally itself given a vinyl reissue, a few months ago.

Friday, January 26, 2024

Gavin Bryars | The Sinking of the Titanic [live]

The Sinking of the Titanic [live]

Brussels, Belgium: Les Disques du Crepuscule, 1991

1:00:13 Audio CD

Edition size unknown

The original 1975 Obscure Records issue of this piece (remastered and collected in the new box set) is 24:28 long, in part because of the limitations of the format - fidelity loss occurs with a vinyl record beyond 25 minutes a side, because of the necessity of cutting the grooves so close together.

With the advent of the Compact Disk format, Byars was able to release a recording of just over an hour, without having to break it up over two sides of an LP. This is a live performance in a disused water tower in the Chateau D'Eau, Bourges, from April of 1990.

The musicians performed from the basement of the three storey tower, where the public heard the pieces through a specially designed sound system on the second floor, after the sound had passed through the cavernous top floor.

The recording was released by Les Disques du Crépuscul, an independent record label founded in 1980 by Michel Duval and Annik Honoré, the journalist best known for her relationship with Joy Division’s Ian Curtis. The label distributed Factory Records artists in Belgium and also worked with Cabaret Voltaire, Mikado, Anna Domino, and Michael Nyman (Obscure #6).

The new Obscure Records box set is easily the most I’ve spent on a single music purchase (even divided by ten for each LP). Previously that distinction was held by this disc. I had been searching for the record for years and finally came across it the reissue by chance. I think I paid $50 for it, which was more than twice the going rate for catalogue compact disks, and three times the price of a new release. Taking inflation into account the amount is probably closer to a hundred dollars. But I didn’t hesitate. A couple of years later, it was reissued in a broader release.

“A number of new elements were used in this performance. The strings comprise two violas and double bass, rather than the string sextet of three violins, two cellos and bass, and additional music was written for them. Percussion was used extensively for specific effects - the hymn tune on marimba, the woodblocks giving the sequence of morse, the use of the bell and bass drum relating to specific aural images. The wind instruments gave a sequence of hymn possibilities as well as delay effects. Quite dramatically, a bass clarinet ‘lament’ was added in homage to the young Scottish piper who died in the disaster. Specific sound effects were added relating to the descriptions given by survivors of particularly striking sounds. There are reminiscences about the disaster from two survivors, Miss Eva Hart and Miss Edith Rusell.”

- Gavin Bryars, liner notes to this edition

Thursday, January 25, 2024

Gavin Bryars | The Sinking of the Titanic

Gavin Bryars

The Sinking of the Titanic

London, UK: Obscure Records, 1975

12” vinyl LP

Edition size unknown

My favourite record and second favourite artwork of all time is the first release on Obscure Records, originally released almost fifty years ago, and just now reissued as part of the mammoth box set of the complete recordings (see previous posts and the many that follow).

It is rare that a work is conceptually sound and also emotionally moving, perhaps more so in audio art and experimental composition. But here are two such works on one LP.

Reportedly issued in an edition of 2000 copies, there were later repressings and reissues in 1976, 1978 and 1982, lending credence to Bryars concerns that he never received royalties. The record then went dark for a decade, becoming increasingly difficult to track down. Then a series of expanding re-releases came out and I now own several different recordings of the piece (see above, centre).

I wrote about "The Sinking of the Titanic" for the Power Plant gallery in Toronto, whose website was running a series of texts by artists about works that were influential to their practice. That text is below.

"The RMS Titanic sank one hundred years ago next April and, famously, the band went down with the ship. There are numerous accounts of the sextet1 continuing to perform after the steamship began sinking, and no accounts of them ever stopping. Composer Gavin Bryars therefore presupposes is that maybe they didn't? “The Sinking of the Titanic” is an open semi-aleatoric sound work that now combines over forty years of investigative research with this initial conceptual presupposition.

The sea-air surface is a perfect reflector, serving as a ceiling that keeps sound underwater. Bryars imagined the Episcopal hymn “Autumn” descending with the ship to the ocean’s bed, becoming trapped there, awaiting excavation. This somewhat fanciful reading of underwater acoustics recalls the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, whose creation of the wireless telegraph was instrumental in the rescue mission for the Titanic. Marconi was convinced that no sound ever dies, it simply becomes fainter and fainter until we can no longer perceive it. He theorized that with sufficiently sensitive equipment one would be able to retrieve sounds made years in the past. He had ultimately hoped to one day hear Christ's Sermon on the Mount.

Bryars applies a series of acoustic treatments to the composition to mimic the echo, deflection phenomena, and the high frequency reduction of sounds underwater. Over the years other elements have been added to the string ensemble - snippets of pre-recorded voices, a bass clarinet, a euphonium, turntablist Philip Jeck, a water-tower, and a string quartet made up of the composer’s children. Each performance is somewhat different than it’s predecessor, and conceivably entirely different. The piece was designed in such a way that one performance may share no musical information with another, yet still be identifiable as the same work. The score for the piece is not fixed musical notation, but rather a large collection of data pertaining to the historical event.

Conceived in 1969 as “the musical equivalent of a work of concept art”, the work was originally not intended to be performed. Bryars gathered a large collection of music related information about the disaster - survivors accounts, technical research on the ship, statistical data, etc. - and sketched out his hypothesis for the sound of the submerged hymn. It was not performed until 1972 and another three years after that it was recorded and released as an LP as part of Brian Eno’s Obscure label. The disk was the first in a series of ten records that included, amongst others, works by John Cage, The Penguin Café Orchestra, Harold Budd, Michael Nyman, John Adams and Eno himself. “The Sinking of the Titanic” was then a twenty-four and a half minute piece, backed with the equally brilliant “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet”.2 When CD technology made longer recordings possible, entirely new versions were released in 1990, 1994 and 2008. The longest, at 72:35, is nearly three times the length of the original recording.

While somewhat atonal in places, the work sits fairly comfortably in the canon of beautiful and functional ambient music, with rich overtones and, ahem, glacial pacing. If anything, it takes the axiom of ambient music (that it does not demand the listener’s attention, but rewards it) several steps further, and beyond the merely aural. The composition retains its power long after works by many of Bryars’ contemporaries have begun to sound dated, at least in part because of the intellectual rigour and the emotional intimacy.

Conceptually and structurally, the work shares qualities with Rodney Graham's 1990 epic “Parsifal”, which has also been presented as a printed score, a reading machine, silkscreen poster and eventual CD recording. Both works could be viewed as musical archeology, originating with historical research and subtle intervention, creating seemingly infinite sonic possibilities – Bryars’ piece will forever bounce around the seabed, and Graham’s looping structure is scheduled to outlast the sun. In fact Graham’s asynchronous loops owe much to the second side of Brian Eno’s “Discreet Music” (Obscure, 1975), which Bryars helped arrange and conduct.

During my own efforts to create resonant works that weave legend, rumour and speculation into a score-based practice, Bryars’ 1969 masterpiece is rarely far from mind. His meticulous research, use of malleable time and implied narrative have served as a model for re-investing in shared stories that grow richer with each reverberation."

- Dave Dyment, 2011

1. The ship’s band was originally an octet but the two pianists were unable to play after relocating to the deck without their instruments.

2. “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet” consists of a thirteen-bar loop of a homeless man singing a religious refrain, from unused documentary footage, accompanied by a string and brass ensemble. Like “…Titanic” it was also later released as a 74 minute expanded version.

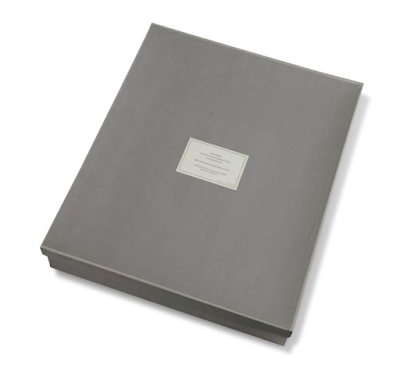

The Complete Obscure Records Collection 1975-1978

[Gavin Byars, John Cage, Brian Eno, Michael Nyman, etc.]

The Complete Obscure Records Collection 1975-1978

Milan, Italy: Dialago, 2023

33 x 33 x 7 cm.

Edition of 1000 numbered copies

For my money (a not insubstantial amount, here) this collection represents Brian Eno at his very, very best. Not just Discreet Music (Obscure #3) - which I’ll take over Music for Airports as his single finest recording - but also the label itself, and it’s entire output, collected here. This is Eno as curator, as evangelist, as collaborator, and as thinker.1

Obscure Records published ten albums between 1975 and 1978, most of them excellent, a few of them sublime. The esoteric boutique “Special Price" label began as an outlet to diseminate the work of overlooked experimental composers, and as a way for Eno to leverage his profile at Island Records to satisfy his wider interests. Eschewing truly difficult and dissonant works, he selected pieces that were certainly outside the mainstream, but that might have the potential to reach larger audiences.

“The music on Obscure was not turbulent or wildly confrontational,” writes David Toop (Obscure 4#) in the new set’s liner notes, “but it did signal a rejection of certain well-established trends in 20th century modernism - the world of serialism, high seriousness, ultra-complex scores, academic electro-acoustic music and free jazz.”

"The main decision is whether I like a piece or not,” Eno told Time Out magazine in 1975, who called the label "the best thing to have happened in the British industry since LPs.” Island Records bankrolling the project was an act of faith, but for Eno it was religion. He was convinced that the intersection of pop music and experimental composition was the most compelling area, and that others might come to agree, given the right promotion.

A meagre £6,000 was not the ideal figure for such promotion, but the shoestring budget allowed the label to move forward without much interference from Island. Eno had similarly promised them that he could record four discs - in the off-hours at the studio - for the cost of one pop record. He often served as producer and ended up designing the album covers himself, also.

Record labels with a strong visual identity (SST, 4AD, Factory, etc.) help inspire loyalty among listeners, and it may have been this rationale (and not the minuscule budget) that led to all ten LPs being issued with an almost uniform cover. They all feature the same cover graphic - a collage by John Bonis - which has been overprinted with black ink, distinguished only by different window reveals on each. This also helps each individual album feel like it is a piece of a larger puzzle.2

Eno enlisted composer Gavin Bryars and Michael Nyman to to assist in the selection of material, and also to contribute albums themselves. The resulting ten discs featured works by John Adams, Bryars, Harold Budd, John Cage, Max Eastley, Eno, Christopher Hobbs, Nyman, the Penguin Café Orchestra, Jan Steele, David Toop, John White, and the painter Tom Phillips, who had introduced Eno to avant-garde music at the Ipswich Civic College.

Bryars also proposed projects by Scratch Orchestra mainstay Howard Skempton, James Tenney, Ingram Marshall, Daniel Lentz, and Michael Byron. Some were rejected outright, and others fell victim to the realities of running a record label as a side hustle.

In a letter to Robert Wyatt (who provides some vocals on Obscure #5), Eno outlined some of his larger plans for the label:

"I have thought of a few interesting projects for Obscure records. The first is to invite fifty composers from all traditions each to write a piece of music beginning in C and ending in G and observing a metronome pulse of sixty. Then we’d perform them all and link them all together to make an album . . . Recently I’ve been more and more impressed by the old jazz session technique of recording, and I think we might well flourish under those circumstances. Or an alternative is to use the jazz session approach and then overdub onto it in the rock sixteen-track style. Another idea that I thought might be nice is some- thing of this nature – “Popular Music arranged by Unpopular Com- posers” – so it would include “Duke of Earl” arranged by Gavin Bryars, “Not Fade Away” arranged by Robert Fripp, “Louie Louie” arranged by Fred Frith, etc., etc., etc. Or alternatively it could use only songs based on the “Louie Louie” chord progression.”

Sadly, none of these projects came to fruition.

Eno’s increasing profile both helped and hindered the series. Bryars recalls in the liner notes that it became shorthand amongst his peers when they were too busy or unavailable to joke “I can’t, I’m in Berlin recording with Bowie!”. The label ceased operations when Eno moved to New York City, and not entirely without acrimony.

I interviewed Bryars once and brought up the slight sense of animosity I perceived when he spoke about Eno and Obscure.

“Nobody got paid!” he replied, testily. He alleged that no contracts were ever issued, only handshake agreements, even after Island was absorbed into the Polygram group in 1976. Artists reportedly never saw sales reports or royalties. “We got paid for doing the sessions and that was it."

A brief lawsuit followed, but it was determined that recoupable losses were too insignificant to continue.

Bryars apparently spearheaded the efforts of this re-release, though his liner notes still betray his frustrations. However, he is quoted in David Sheppard’s book On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno, acknowledging the impact on his career: "Brian definitely went out on a limb. He backed something that was certainly not fashionable, we weren’t very well known and were even despised by the musical establishment. Those Obscure records were important – the reason many of us were able to work outside of England for example. Brian led us into all sorts of unexpected territory – and led a lot of unexpected people into our territory too.”

For his part, Eno has only ever had good things to say about Bryars: "I’ve always liked Gavin, and in my opinion his influence on the music scene has been greater than he’s given credit for.”

“I primarily started the label to release those two pieces of Gavin’s that came out on the first album,” Eno is quoted in Bradford Bailey’s liner note text. “I thought they were such great pieces of music and the story associated with them was so powerful, that I felt like a lot of people would like them if they were actually able to hear them”.

He was not wrong: The A-Side has been reissued several times (see next post) and the B-side3 hit number one on the classical charts, almost twenty years later (with a little help from the star power of Tom Waits).

But Bryars' LP was not successful upon initial release, and only two of the ten sold in numbers that would make Island pleased about their investment: Eno’s own Discreet Music, and The Music of the Penguin Cafe.

But as a brief vanity label (as it might have been pejoratively called) it was remarkably consistent and achieved its goal of bringing greater attention to these artists.

Bryars went on to a successful career as a composer and performer. Nyman sold three million copies of his soundtrack to Jane Campion’s 1993 film The Piano. Harold Budd increased his profile with future collaborations with Eno, and later the Cocteau Twins. The Penguin Cafe Orchestra performed together for 24 years and after founding member Simon Jeffes died his son Arthur continued the project with the abbreviated name Penguin Cafe. PCO songs have appeared in numerous films, from directors ranging from John Hughes to Oliver Stone. David Toop collaborated with the Flying Lizards, Thurston Moore, Bob Cobbing, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Camille Norment, Akio Suzuki and Elaine Mitchener. He is also the author of several books on Hip-Hop, Ambient Music and Audio Art. Tom Philips (who died exactly a year before this reissue was released) was awarded an OBE in 2002.

This deluxe new box set collects all ten recordings and a 126-page booklet featuring new essays by Bryars (The History), Bradford Bailey (The Obscure Sounds Of A Quiet Revolution), Max Eastley (Sculpture In The Recording Studio, 1978), Richard Bernas (John Cage's "Voices And Instruments"), Tom Recchion (Epiphanies) and Walter Rovere.

Housed in a lavish linen-covered clamshell box and released in a numbered edition of 1000, this feels more like an art edition than a collection of records. It’s a massive set (it took me a while to find the right place to store it, it’s larger than my turntable) with a price-tag to match4. It warrants several posts, so - for the next week (time permitting) I’ll feature a quick write up of each of the ten recordings. Obscure #1 alone, requires several posts, to accommodate it’s A and B-side, and the various reissues of both.

1. Obscure Records appears only as a footnote in the two main published volumes about Eno’s work: Eric Tamm’s Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound and Christopher Scoates’ Brian Eno: Visual Music. David Sheppard’s biography On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno dedicates a couple of pages to the label.

2. Later reissues of Eno’s Discreet Music, Harold Budd’s The Pavillion of Dreams and Music from the Penguin Cafe all had new covers.

3. The idea of a musician or band being defined by a b-side holds great appeal to me, for some reason. I once had a longer list, but “How Soon is Now” by the Smiths and “Dear God” by XTC come to mind.

4. My only gripes: the steep, steep price tag, wasting a good chunk of the book reprinting redundant liner notes that are already available on the facsimile LP sleeves, and the hefty customs charge I was not expecting (Amazon.ca did not state it was arriving from Germany).

"Arriving just in time for the festive period, The Complete Obscure Records Collection is confirmation that Santa believes I have been a good boy this year. It’s still remarkable to think what a different music ‘business’ existed some 50 years ago, and how a label such as this could even have existed. Obscure Records was initially conceived by Brian Eno as a vehicle for the work of his yet to be recorded friend, Gavin Bryars, before taking on grander ambitions. Having just departed Roxy Music in 1973, Eno became fascinated with the dynamic London experimental music scene, and even participated himself, with Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra and Portsmouth Sinfonia. Originally issued between 1975 and 1978, these recordings remain inspirational, important and groundbreaking. Indeed, the first suite of works: Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic, Christopher Hobbs, John Adams, and Gavin Bryars’ Ensemble Pieces, Brian Eno’s Discreet Music, David Toop and Max Eastley’s New and Rediscovered Musical Instrument - are all essential listening for openminded souls. Though you may have some of these recordings, the majority have been out of print for years, with a number having never received a CD reissue. The vinyl and CD sets are accompanied by a lavishly illustrated booklet, with rare photos, archival material and texts by Gavin Bryars, Bradford Bailey, David Toop, Max Eastley, Richard Bernas, and Tom Recchion. Finally, the fantasy of this set ever existing, is a reality."

- Robin Rimbaud

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)