[Gavin Byars, John Cage, Brian Eno, Michael Nyman, etc.]

The Complete Obscure Records Collection 1975-1978

Milan, Italy: Dialago, 2023

33 x 33 x 7 cm.

Edition of 1000 numbered copies

For my money (a not insubstantial amount, here) this collection represents Brian Eno at his very, very best. Not just Discreet Music (Obscure #3) - which I’ll take over Music for Airports as his single finest recording - but also the label itself, and it’s entire output, collected here. This is Eno as curator, as evangelist, as collaborator, and as thinker.1

Obscure Records published ten albums between 1975 and 1978, most of them excellent, a few of them sublime. The esoteric boutique “Special Price" label began as an outlet to diseminate the work of overlooked experimental composers, and as a way for Eno to leverage his profile at Island Records to satisfy his wider interests. Eschewing truly difficult and dissonant works, he selected pieces that were certainly outside the mainstream, but that might have the potential to reach larger audiences.

“The music on Obscure was not turbulent or wildly confrontational,” writes David Toop (Obscure 4#) in the new set’s liner notes, “but it did signal a rejection of certain well-established trends in 20th century modernism - the world of serialism, high seriousness, ultra-complex scores, academic electro-acoustic music and free jazz.”

"The main decision is whether I like a piece or not,” Eno told Time Out magazine in 1975, who called the label "the best thing to have happened in the British industry since LPs.” Island Records bankrolling the project was an act of faith, but for Eno it was religion. He was convinced that the intersection of pop music and experimental composition was the most compelling area, and that others might come to agree, given the right promotion.

A meagre £6,000 was not the ideal figure for such promotion, but the shoestring budget allowed the label to move forward without much interference from Island. Eno had similarly promised them that he could record four discs - in the off-hours at the studio - for the cost of one pop record. He often served as producer and ended up designing the album covers himself, also.

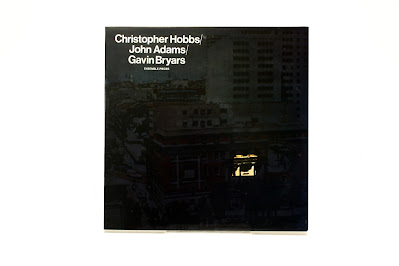

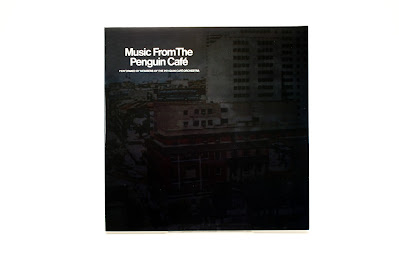

Record labels with a strong visual identity (SST, 4AD, Factory, etc.) help inspire loyalty among listeners, and it may have been this rationale (and not the minuscule budget) that led to all ten LPs being issued with an almost uniform cover. They all feature the same cover graphic - a collage by John Bonis - which has been overprinted with black ink, distinguished only by different window reveals on each. This also helps each individual album feel like it is a piece of a larger puzzle.2

Eno enlisted composer Gavin Bryars and Michael Nyman to to assist in the selection of material, and also to contribute albums themselves. The resulting ten discs featured works by John Adams, Bryars, Harold Budd, John Cage, Max Eastley, Eno, Christopher Hobbs, Nyman, the Penguin Café Orchestra, Jan Steele, David Toop, John White, and the painter Tom Phillips, who had introduced Eno to avant-garde music at the Ipswich Civic College.

Bryars also proposed projects by Scratch Orchestra mainstay Howard Skempton, James Tenney, Ingram Marshall, Daniel Lentz, and Michael Byron. Some were rejected outright, and others fell victim to the realities of running a record label as a side hustle.

In a letter to Robert Wyatt (who provides some vocals on Obscure #5), Eno outlined some of his larger plans for the label:

"I have thought of a few interesting projects for Obscure records. The first is to invite fifty composers from all traditions each to write a piece of music beginning in C and ending in G and observing a metronome pulse of sixty. Then we’d perform them all and link them all together to make an album . . . Recently I’ve been more and more impressed by the old jazz session technique of recording, and I think we might well flourish under those circumstances. Or an alternative is to use the jazz session approach and then overdub onto it in the rock sixteen-track style. Another idea that I thought might be nice is some- thing of this nature – “Popular Music arranged by Unpopular Com- posers” – so it would include “Duke of Earl” arranged by Gavin Bryars, “Not Fade Away” arranged by Robert Fripp, “Louie Louie” arranged by Fred Frith, etc., etc., etc. Or alternatively it could use only songs based on the “Louie Louie” chord progression.”

Sadly, none of these projects came to fruition.

Eno’s increasing profile both helped and hindered the series. Bryars recalls in the liner notes that it became shorthand amongst his peers when they were too busy or unavailable to joke “I can’t, I’m in Berlin recording with Bowie!”. The label ceased operations when Eno moved to New York City, and not entirely without acrimony.

I interviewed Bryars once and brought up the slight sense of animosity I perceived when he spoke about Eno and Obscure.

“Nobody got paid!” he replied, testily. He alleged that no contracts were ever issued, only handshake agreements, even after Island was absorbed into the Polygram group in 1976. Artists reportedly never saw sales reports or royalties. “We got paid for doing the sessions and that was it."

A brief lawsuit followed, but it was determined that recoupable losses were too insignificant to continue.

Bryars apparently spearheaded the efforts of this re-release, though his liner notes still betray his frustrations. However, he is quoted in David Sheppard’s book On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno, acknowledging the impact on his career: "Brian definitely went out on a limb. He backed something that was certainly not fashionable, we weren’t very well known and were even despised by the musical establishment. Those Obscure records were important – the reason many of us were able to work outside of England for example. Brian led us into all sorts of unexpected territory – and led a lot of unexpected people into our territory too.”

For his part, Eno has only ever had good things to say about Bryars: "I’ve always liked Gavin, and in my opinion his influence on the music scene has been greater than he’s given credit for.”

“I primarily started the label to release those two pieces of Gavin’s that came out on the first album,” Eno is quoted in Bradford Bailey’s liner note text. “I thought they were such great pieces of music and the story associated with them was so powerful, that I felt like a lot of people would like them if they were actually able to hear them”.

He was not wrong: The A-Side has been reissued several times (see next post) and the B-side3 hit number one on the classical charts, almost twenty years later (with a little help from the star power of Tom Waits).

But Bryars' LP was not successful upon initial release, and only two of the ten sold in numbers that would make Island pleased about their investment: Eno’s own Discreet Music, and The Music of the Penguin Cafe.

But as a brief vanity label (as it might have been pejoratively called) it was remarkably consistent and achieved its goal of bringing greater attention to these artists.

Bryars went on to a successful career as a composer and performer. Nyman sold three million copies of his soundtrack to Jane Campion’s 1993 film The Piano. Harold Budd increased his profile with future collaborations with Eno, and later the Cocteau Twins. The Penguin Cafe Orchestra performed together for 24 years and after founding member Simon Jeffes died his son Arthur continued the project with the abbreviated name Penguin Cafe. PCO songs have appeared in numerous films, from directors ranging from John Hughes to Oliver Stone. David Toop collaborated with the Flying Lizards, Thurston Moore, Bob Cobbing, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Camille Norment, Akio Suzuki and Elaine Mitchener. He is also the author of several books on Hip-Hop, Ambient Music and Audio Art. Tom Philips (who died exactly a year before this reissue was released) was awarded an OBE in 2002.

This deluxe new box set collects all ten recordings and a 126-page booklet featuring new essays by Bryars (The History), Bradford Bailey (The Obscure Sounds Of A Quiet Revolution), Max Eastley (Sculpture In The Recording Studio, 1978), Richard Bernas (John Cage's "Voices And Instruments"), Tom Recchion (Epiphanies) and Walter Rovere.

Housed in a lavish linen-covered clamshell box and released in a numbered edition of 1000, this feels more like an art edition than a collection of records. It’s a massive set (it took me a while to find the right place to store it, it’s larger than my turntable) with a price-tag to match4. It warrants several posts, so - for the next week (time permitting) I’ll feature a quick write up of each of the ten recordings. Obscure #1 alone, requires several posts, to accommodate it’s A and B-side, and the various reissues of both.

1. Obscure Records appears only as a footnote in the two main published volumes about Eno’s work: Eric Tamm’s Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound and Christopher Scoates’ Brian Eno: Visual Music. David Sheppard’s biography On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno dedicates a couple of pages to the label.

2. Later reissues of Eno’s Discreet Music, Harold Budd’s The Pavillion of Dreams and Music from the Penguin Cafe all had new covers.

3. The idea of a musician or band being defined by a b-side holds great appeal to me, for some reason. I once had a longer list, but “How Soon is Now” by the Smiths and “Dear God” by XTC come to mind.

4. My only gripes: the steep, steep price tag, wasting a good chunk of the book reprinting redundant liner notes that are already available on the facsimile LP sleeves, and the hefty customs charge I was not expecting (Amazon.ca did not state it was arriving from Germany).

"Arriving just in time for the festive period, The Complete Obscure Records Collection is confirmation that Santa believes I have been a good boy this year. It’s still remarkable to think what a different music ‘business’ existed some 50 years ago, and how a label such as this could even have existed. Obscure Records was initially conceived by Brian Eno as a vehicle for the work of his yet to be recorded friend, Gavin Bryars, before taking on grander ambitions. Having just departed Roxy Music in 1973, Eno became fascinated with the dynamic London experimental music scene, and even participated himself, with Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra and Portsmouth Sinfonia. Originally issued between 1975 and 1978, these recordings remain inspirational, important and groundbreaking. Indeed, the first suite of works: Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic, Christopher Hobbs, John Adams, and Gavin Bryars’ Ensemble Pieces, Brian Eno’s Discreet Music, David Toop and Max Eastley’s New and Rediscovered Musical Instrument - are all essential listening for openminded souls. Though you may have some of these recordings, the majority have been out of print for years, with a number having never received a CD reissue. The vinyl and CD sets are accompanied by a lavishly illustrated booklet, with rare photos, archival material and texts by Gavin Bryars, Bradford Bailey, David Toop, Max Eastley, Richard Bernas, and Tom Recchion. Finally, the fantasy of this set ever existing, is a reality."

- Robin Rimbaud

RECOVER A STOLEN BTC BY BLISS PARADOX RECOVERY.

ReplyDeleteOver 3 years of research about a reputable recovery company to reclaim defrauded bitcoin, I came across Bliss Paradox recovery which remained the best and renown recovery firm that victims which have been defrauded can trust and work with.

Thanks to them. I was left no other choice but to admit that funds recovery is real. Contact details you can reach out to. Mail: Blissparadoxrecovery @ aol. com, Telegram: Blissparadoxrecovery

Regards!

ReplyDeleteHave you invested in fake binary options, forex trading, or a fraudulent trading platform? If so, don’t worry, because Chris Frankly Asset Recovery and its team can help you recover your stolen funds. With all the information you need, Captain Jack has successfully recovered numerous cases of clients losing their hard-earned money to fraudulent online investment platforms. If you need help recovering your stolen funds, contact Chris Frankly Asset Recovery today via email: cfranklyassetrecovery@gmail.com