William N. Copley was an American painter, gallerist, collector, publisher and philanthropist, born on January 24, 1919. The adopted son of a newspaper magnate, Copley studied at Yale University before being drafted into the Second World War.

In 1946, his brother-in-law John Ployardt, a Canadian-born animator and narrator, introduced him to painting and Surrealism. After a night of drinking, the two decided to open a gallery and, “in the white haze of the morning after” were both “too proud to perish the thought.”

Copley sold his house, Ployardt quit his job at Disney, and they rented a bungalow at 257 North Canon Drive in Beverly Hills (now a parking lot). A brass plaque inscribed “Copley Galleries” was produced, at a cost of $250. A pet capuchin monkey was bought to serve as a gallery mascot, until it escaped. It was replaced with a cockatiel. “The bird was sweet and tame, and bird shit was easier to deal with than monkey shit,” Copley noted.

He convinced a number of artists to present their work at Copley Galleries, including René Magritte, Yves Tanguy, Joseph Cornell (his first ever gallery exhibition), Man Ray, Roberto Matta and Max Ernst. Despite the stellar line-up, sales were poor, as Los Angeles audiences had not yet warmed to Surrealism the way they had in New York. “I think I sold two pictures. I was trying to sell Cornell for $200. Just couldn't do it. So I went out of business,” Copley told Paul Cummings, in 1968.

Copley’s failure as a salesman led to his success as a collector. Having guaranteed the artists that at least ten per cent of the exhibition would sell, Copley found himself buying a number of the works for himself. For example, he purchased Man Ray’s Observatory Time: The Lovers from 1936, for $500. The eight-by-three-foot painting of red lips floating above the landscape has subsequently been called “the quintessential Surrealist painting.”

After the gallery closed, he remained friends with many of the artists, and became particularly close with Marcel Duchamp, who he was introduced to by Man Ray. “It was Duchamp and Max Ernst who really encouraged me to continue painting,” he recounted.

In 1949, Copley left his wife and children and relocated to Paris, to pursue painting full-time. He held his first solo exhibition in 1951, at age 32. National and international solo and group exhibitions followed, including a solo turn at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and contributions to documenta 5 and 7.

With his second wife, Norma Rathner, he developed the William and Norma Copley Foundation, with further money he inherited after the death of his father. The organization, of which Duchamp was a board member, offered small grants to artists and musicians. When Duchamp died in 1968, the Foundation donated his final work, L’Etant Donnes, to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it remains today.

Copley eventually amassed one of the world's most highly regarded collections of Surrealist art, which was sold at auction in 1979. The Man Ray work purchased for $500 fetched $750,000, and the entire lot sold for $6.7 million, a record at the time, for single owner’s collection in the United States.

In the mid-sixties, Copley befriended the Surrealist and Dada painter Dmitri Petrov, then-based in Philadelphia. The pair decided to publish mail-order portfolios of work by contemporary artists out of a New York City Upper West Side loft. Inspired by Fluxus and notions of 'blurring the boundaries between art and life', they were determined to produce high-quality serial artworks which could bypass the museum and gallery system and reach buyers directly.

The plan was to produce a folder, designed by an artist, bi-monthly, which would contain works by several other artists, offered by subscription. Every artist received the same payment - $100 per submission.

Began at a time of much political unrest, the title S.M.S. (unfortunately) stands for ‘Shit Must Stop’, though mostly as an inside joke. Their publishing name, the considerably more distinguished sounding ‘The Letter Edged in Black Press Incorporated’, came from the suggestion of a lawyer. It is presumably a reference to the Country/Folk song of the same name, which has been recorded by Slim Whitman, Chet Atkins, Jim Reeves, Johnny Cash and others.

The loft production studio was reportedly lavish. It featured an open bar, a full buffet regularly replenished by the nearby Zabar's Delicatessen, and a pay-phone with complimentary dimes, housed in a cigar box. The place became a hotbed of activity. “On a given day, you never knew who would show up,” remembers Lew Syken, the project's chief designer.

The place was often packed with students, tasked with some of the more laborious production concerns, such as opening 8,000 letters sent to Copley from H.C. Westermann for portfolio No. 3, or to burn 2,000 of Lil Picard's bowties for the following issue. Copley occupied an office in the third floor loft with a view of West 80th Street and Broadway, and Petrov handled the day-to-day, often round-the-clock production schedule.

While the high-cost of producing the often intricate and elaborate works led to the closing of S.M.S. after a year, the six portfolios they produced rank among the most important Artists’-Multiples-as-Periodicals ever produced.

The portfolios included works by artists both well-renowned and obscure, including Arman, Enrico Baj, James Lee Byars, John Cage, Christo, Bruce Conner, Hollis Frampton, John Giorno, Richard Hamilton, Dick Higgins, Roy Lichtenstein, Lee Lozano, Bruce Nauman, Claes Oldenburg, Meret Oppenheim, Man Ray, Terry Riley, Dieter Roth, Robert Watts, Lawrence Weiner, La Monte Young, and others.

The covers were designed by Marcel Duchamp, Irving Petlin, John Battan, Robert Stanley, Richard Artschwager, and (possibly as a nod to Copley’s previous gallery mascot) Congo the Chimpanzee. The famous painting chimp was also included in the Fluxus Year Box 1, an early influence on S.M.S.

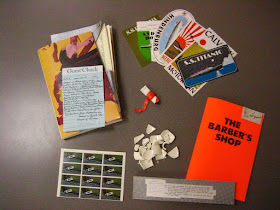

Roy Lichtenstein contributed a folded paper hat. Yoko Ono’s Mend Piece for John was a broken tea cup to be repaired with the supplied glue and three-stanza poem. Deiter Roth contributed a chocolate bar. Other formats included decals, folders, index cards, cut-outs, accordion folds, acetates, pill capsules, games, records, photo albums, and penakistiscope.

Although he only contributed one work to the series (a fascinating folder called The Barber's Shop), Copley presumably viewed the project as an extension of his work as an artist, personally signing each issue ‘CPLY’ (pronounced 'see ply', this was the name with which he signed his own paintings).

In total, 73 original multiples were produced for the 6 portfolios. 2000 copies of each were produced, and reportedly 1500 distributed. In 1981, Copley donated the remaining 500 sets of SMS to the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York City. These were presumably stored and forgotten, until a flood hit, destroying many of them.

In 1998, in collaboration with Reinhold-Brown gallery, the New Museum offered complete sets of the periodical for the first time in almost two decades. They included the original mailing case, as well as two works that were produced in 1968 but never distributed: boxed audio cassettes by minimalists Terry Riley and La Monte Young. Collectors could also elect to have the portfolios housed in new custom-made plexiglass slipcases.

Most of the information about SMS comes from a slim, 16-page black and white catalogue produced at the time, including some of the oft-told legends recounted above. S.M.S. is worthy of it's own monograph, but very little has been published about the project. It's completely omitted in Phil Aarons' In Numbers: Serial Publications by Artists Since 1955 and receives only brief mention in Gwen Allen's Artists' Magazines. Conversely, the similar Aspen Magazine gets a full chapter in Allen's book.

Aspen preceded S.M.S. by a couple of years, but didn't fully break away from the standard magazine format: Aspen commissioned writers to write about art, and included advertisements. Their format was less conventional than SMS (there was no standard size or approach for their box or folder) but the quality was also less consistent. The strength of the individual issues rested on the quality of the guest editors, who included Andy Warhol, Marshal McLuhan, Brian O’Doherty, Jon Hendricks, Dan Graham and Angus MacLise. While these issues are incredibly strong, the contents of the first and final Aspen hold little interest in terms of contemporary artists’ books, and multiples. (For more information on Aspen, see previous posts, here).

Copley's wealth meant that he could avoid the need for advertising (which itself proved tricky for Aspen, whose later issues did away with them altogether), but the decision not to publish art criticism in an art magazine speaks volumes as to Copley’s vision of what a periodical could be.

The New Museum Shop has some of the individual SMS items still available, with prices ranging from $50 to $300, with the Duchamp cover and works by Richard Hamilton, Yoko Ono and La Monte Young/Marian Zazeela selling at the higher end. They are available at the gallery’s website, here.

A friend has generously loaned me the complete set of the stunning periodicals, and I have been documenting the works individually. I'll be posting them sporadically over the next few months, tagged SMS.

No comments:

Post a Comment